SoCal automotive

Fins

A beach read needs sex to sizzle, and let’s face it…what’s sexier than fins?

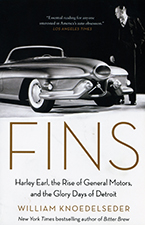

Disappointingly for ichthyologists and swim fetishists, the fins in question today are automotive. The book in question is Fins by William Knoedelseder, which is a loosely structured biography of Harley Earl, the autocratic chief designer at General Motors for much of the twentieth century. Along the way, the book sweeps up all sorts of trivia about the early days of motoring and, as we shall see, Hollywood. The volume has obvious appeal to gearheads and design freaks, and its polyglot approach brings in anyone else with an interest in trivia. I mean, who doesn’t want to lie on a beach and read about corporate infighting over clay models?

It pains me to realize this, but some of you are young enough to have no idea what an automotive fin is. Fear not: samples abound, if you click the little blue links.

No book about the automotives can open anywhere but Michigan, and so our author does. Pre-automobile, Michigan’s commercial draws were its farmland and, especially, its enormous stands of forest. In that context, we meet Harley Earl’s father, J.W. As a young man, J.W. was a Michigan logger, a job that was every bit as much fun as it sounds. On a break J.W. went to California to visit family who lived in Arcadia, near Los Angeles. J.W. decided logging and winter were for the birds and found a job building carriages (as in horse-drawn carriages) in L.A. It was 1887.

Into this bucolic picture, inject Henry Ford and Ransom Olds.

Ford and Olds were the most successful of the early inventors of the automobile. The public loved their vehicles, which set both a business problem, and in its solution, a pattern that dominates the industry even today: in order to scale up rapidly, both Ford and Olds decided to farm out production of major subassemblies to suppliers and focus their own efforts on final assembly. (Ford's soup-to-nuts Rouge River plant came later.) Significant to our tale, one of those subassemblies was the automobile’s body, its coach.

This approach led to a highly innovative period in American motoring. The innovation came not from the manufacturers, whose coaches were an afterthought to engineering and mass production. The resulting products were angular and slightly crude. A trade developed in which the more affluent would buy just a powertrain and chassis from the manufacturer, take delivery, and then have a custom body built on top of it. The result, largely hand-constructed, had a rounded, fluid appearance that the mass-produced products lacked. You can see where this is going…by now the Earls were living in Hollywood (the family manse was actually on Hollywood Boulevard, they had to move when the city zoned the street commercial), Hollywood loved custom automobiles, and J.W. soon found himself in the custom auto body business. Earl Carriage Works became Earl Automotive Works.

For the record: Mary Pickford, “America’s Sweetheart,” was a gearhead. Drove a Mercer Raceabout she named “Fifi,” the woman was addicted to velocity. It was 1913.

If Hollywood was going gearhead, J.W.’s son Harley had gone about as Hollywood as you could get. He attended, but did not graduate from, USC. He hung out with the Chandlers, the publishers of the influential Los Angeles Times. Working for his father, he built custom bodies for a list of stars, including Pickford and her husband, Douglas Fairbanks. Harley’s custom body for Fatty Arbuckle took six weeks, our author tells us, for the multiple coats of paint alone. Many of these bodies were built on Cadillac chassis. Don Lee Cadillac, the sole Cadillac dealer for California, with locations throughout the state, was only a few doors down from Earl Automotive Works. Lee was impressed enough with Harley’s work (by now J.W. had stepped back from Harley’s “glorified hotrod shop”) that he bought Earl Automotive Works. He also recommended to General Motors that they bring Harley on as an employee.

GM brought Harley to Detroit on a trial basis to do styling for a new vehicle they were planning to add to Cadillac Division, the La Salle. He produced designs for four related body styles for the 1927 La Salle, with sophisticated color schemes that harkened back to his custom work. With typical Detroit drama, the designs were presented to Alfred Sloane, GM’s chairman, and Fred and Larry Fisher, GM’s body supplier of “Body by Fisher™” fame. They were impressed enough to decide on the spot to take both the vehicles and Harley with them to the upcoming Paris Auto Show. Harley and Sloane were opposites in many ways: Harley the elegant chief designer, Sloane a great deal grittier as a Midwest business type. But both had “gasoline in their blood” and they bonded on the boat ride to Europe on both a professional and a social level.

Despite the success of the La Salle, Sloane chose a soft launch for the Styling department at GM. Originally called “Art and Colour,” the department was initially held askance by the engineering-oriented brands (Chevrolet, Pontiac, Oldsmobile, Buick, and Cadillac), who operated with near total autonomy. Sloane did encourage the brands to consult with Harley, however, and when they did, they discovered his talent not just for design, but for saleable design that would appeal to the end customer.

A marriage made in Heaven. Now throw in an unwanted pregnancy and the Great Depression. It was 1929.

The unwanted pregnancy was the 1929 Buick. Harley had designed the side panels to bow out slightly beneath the windows to catch a reflection of the light, then taper back to the body. Somewhere between Harley’s final design and production, the engineers “simplified” the design, by bowing the panel out but not tapering it back in. The result was ungainly…it looked, well, pregnant. Harley had a fit. In more normal times that might have been the end of his career, at least at GM. But the stock market crashed, and Styling proved its mettle at General Motors.

Retooling for a new model is an expensive undertaking. Not only does the manufacturer have to retool the assembly line, its suppliers have to retool their own lines to make revised component parts, things like engines and starters and differentials. (Also window cranks and cupholders.) Sheet metal is one of the cheapest and easiest things to change on a car. Sloane set Harley the task of figuring out how to leverage body design to sell cars (to “move metal” in the parlance) in a tight market. Harley saved the entire Pontiac line by ripping off its new front-end design (the “face”) from Bentley. His beloved LaSalle was next up to be axed, so he built a full-size, trimmed, wood model of a proposed new 1934 LaSalle and bought that mark an additional seven years of life. Instead of getting fired for knocking up the Buick, Harley emerged a driving force at General Motors.

Eagle-eyed readers are of course becoming restless…all of this is very interesting, but where are the fins? For that you needed World War II. It was 1941.

GM’s involvement with the war was extensive, and somewhere in its course Harley and his designers became enamored of the tail section of the P-38 Lightening fighter, with its twin-beam construction and resultant twin tails. Post-war the country was flush with cash and pent-up demand (private auto sales had been suspended during the war), and Harley considered the fin a symbol of that optimism. His design team took the tail detail of the P-38 and gave it a bit of the elegance of a swimming fish’s tail. Harley was dubious about the result…he got the idea, but was afraid the style would be too extreme for the public. But when Alfred Sloane saw a prototype of the 1948 Cadillac with its twin tails on a Detroit proving ground, Sloane declared, “Now you have a Cadillac in the rear as well as the front!” so fins were in for the ‘50s. Our author deems the 1955 Chevrolet Bel Air to be the purest, noblest expression of the form. (Of fins? The boys in Styling can get a tad overwrought.) Harley had an obsession with chrome, which he referred to as “entertainment.” As in, “Let’s give them a little entertainment on the rear quarter panel.” Which is what he did in spades with the iconic 1957 Chevrolet.

Design is a young man’s game, and inevitably even Harley fell behind. He was on an extended trip to Europe when his team caught sight of the 1957 Plymouth. Fins and chrome for days, plus a radical body line that rose to the rear, rather than falling away. In his absence, his team worked up alternate designs to compete with Chrysler. Rather than hitting the roof when he saw them (Harley was nothing if not autocratic), he seemed to realize a sea change, and he told them to continue with the new designs. The torch had been passed.

The torch had been passed in the corporate offices as well. The era of bean counters and safety nerds was just beginning and the era of men with gasoline in their blood was waning. Today the fiction is that cars are just transportation…and fiction it is. Vehicles are about freedom and identity and sex. Skeptics might consider the case of the 1958 Ford Edsel: technologically advanced, supported by an enormous ad campaign, Ford thought to sell 300,000 Edsels in its first year. Instead it tanked. Why? Body styling: the plain fact is that no man on Earth, then or now, wants to be seen driving a vehicle whose grille looks like a vagina.

Tell me again that cars aren’t about sex.

Copyright © The Curmudgeon's Guide™

All rights reserved